Author’s Note

Please refer to a.bhikkhu.pub@gmail.com for correspondence concerning the present work.

Soft copies are available free of charge via:

- (a) https://sasanarakkha.org/teachings;

- (b) https://independent.academia.edu/S%C4%81san%C4%81rakkhaBuddhistSanctuary;

- (c) https://archive.org/details/@s_san_rakkha_buddhist_sanctuary.

- (d) It is, besides a number of other grammars, also available at: https://archive.org/details/@_h_nuttamo_bhikkhu.

Copyright © 2021

Sāsanārakkha Buddhist Sanctuary (SBS)

34000 Taiping, Perak, Malaysia

Tel.: + 60 11-1601 1198;

Web: https://sasanarakkha.org/

Free for non-commercial use, otherwise all rights reserved.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank, first and foremost, ven. Ariyadhammika (Austria) as saṅghanāyaka (“leader of the community”) of Sāsanārakkha Buddhist Sanctuary (SBS), especially for the freedom of schedule and the allowance to pursue my studies in full-time. I also wish to express my thanks to ven. Bodhirasa (South Africa) for pointing out flaws in the chapters “Sandhi” and “Morphology” and to ven. Pāladhammika (U.S.A.) for reading through a preliminary draft, giving perceptive feedback. Sayalay Cālā Therī (Aggācāra International Education and Meditation Centre, Myanmar) readily responded to numerous of my queries with insightful comments. I value and recognize her input. Ven. Sujāta (Germany) and Mrs. Looi Sow Fei (Malaysia) also went through a draft of the entire book; I am thankful for all the mistakes they spotted.

I appreciate and am grateful for the discussions with Dr. Bryan Levman (University of Toronto, Canada) about many points and his exceedingly kind willingness to fully review an earlier draft version – the quality of this work would have suffered much without his suggestions. Despite his teaching obligations, Prof. Dr. Thomas Oberlies (Universität Göttingen, Germany) kindly undertook to review substantial parts of the present grammar; I prize his insightful assistance, without which it would have suffered a sizable degradation in quality as well. I wish to thank Dr. Alastair Gornall for his occasional help. The efforts of Dulip Withanage and his wife Kanchana Ranasinghe (both Sri Lanka) are recognized with gratitude. They helped with needed book scans from the University of Heidelberg’s library, thus being a prop for the completion of my studies. Much thanks is also due to Stefan (Germany) and Lamai (Thailand) Köppl who, in like manner, acted very supportively. May the spiritual merit (puññaṃ) generated with the creation and donation of this work be dedicated to the welfare of Stefan and Laimai Köppl’s recently deceased father (Rudolf Köppl, dec. 2020) and mother (Malai Namnuan, dec. 2021) respectively, all beings as a whole and for the longevity of the Buddha’s teaching: buddhasāsanaṃ ciraṃ tiṭṭhatu – “May the Buddha’s dispensation endure for long!”

Introduction

Grammar and phonetics are a vital part of the indigenous Buddhist traditions, right from the era of the Teacher’s (i.e. the Buddha’s) floruit and throughout history up until modernity, constituting not only the foundation for preaching the dhamma to the people but also for understanding the subtleties of it in the first place (

These two things, bhikkhus, lead to the confusion and disappearance of the good dhamma (saddhammo), which two? Badly- (or “wrongly”, “incorrectly”) settled words and syllables (or “letters”) and misinterpreted meaning. Bhikkhus, the meaning of badly-settled words and syllables is misinterpreted […] These two things, bhikkhus, lead to the continuance of the good dhamma, what two? Well-settled words and syllables and well-interpreted meaning. Bhikkhus, the meaning of well-settled words and syllables is well interpreted (AN II – dukanipātapāḷi, p. 7 [AN 2.20]).Dveme, bhikkhave, dhammā saddhammassa sammosāya antaradhānāya saṃvattanti. katame dve? dunnikkhittañca padabyañjanaṃ attho ca dunnīto. dunnikkhittassa, bhikkhave, padabyañjanassa atthopi dunnayo hoti […] dveme, bhikkhave, dhammā saddhammassa ṭhitiyā asammosāya anantaradhānāya saṃvattanti. katame dve? sunikkhittañca padabyañjanaṃ attho ca sunīto. sunikkhittassa, bhikkhave, padabyañjanassa atthopi sunayo hoti […]

Bearing that in mind, the attempt to elucidate, elaborate upon and enrich the grammar of the Pāḷi language as undertaken with the present work seems a meaningful endeavor.

This Māgadhabhāsā (Pāḷi) grammar, as it is named, was originally not intended to reach the extent it has now. The initial prospect was to create an informal and more or less makeshift conglomerate of relevant material mainly for personal studies and general use. However, the inspiration roused by the thought about the spiritual merit (puññaṃ) gained by creating and sharing something more fundamental and reliable by investing just some extra labor (quite a bit in the end actually) led to the initial makeshift design being worked upon to lose its rough edges and growing in bulk.

With that, the aims, methods and rationales of the present Pāḷi grammar are as follows: (a) Lubricating access to the information contained in numerous modern Pāḷi grammars written in English by collating the dispersed material contained within them. People who wish to learn about grammatical rules and principles – either on a broader spectrum or at all – are compelled to track them down in the thicket of the widely scattered grammar inventories as separately given by the various available grammars. These works, mostly fine and outstanding works of scholarship in their own right, each individually often contain valuable data and perspectives not found in the other ones, and these are attempted to be distilled and presented with this Pāḷi grammar. (b) Facilitating identification of and providing explicit reference to most of the grammatical rules contained in the KaccāyanabyākaraṇaṃAlso Kaccāyanavyākaraṇaṃ: kaccāyana + vyākaraṇaṃ → kaccāyanavyākaraṇaṃ (“the grammar of Kaccāyana”). The 19ᵗʰ century Sri Lankan scholar bhikkhu

- It does not throughout throw into relief the different ancient grammarian’s views and presentations (that of Moggallāna, Aggavaṃsa etc.)

- Some informative modern grammars have not been taken into consideration.

- It does not deal with prosody.

The structure is primarily modelled after that of Kaccāyana and references (incl. page numbers) to works in the Pāḷi language as well as quotations from them are directed to and from the Chaṭṭhasaṅgāyana editions (PDF files) of the Vipassana Research Institute, Igatpuri, India, also commonly known as the Burmese edition (Bᵉ), with the exception of one quotation from a European edition (Eᵉ). Since traditionally proper names and titles of books are not capitalized in the Pāḷi language, this practice is continued here for the actual Pāḷi texts quoted; however, it is, for obvious reasons, discontinued for such individual Pāḷi words contained in the running text written in English.

Those who are not interested in word formation and derivation but mainly wish to have an avenue quickening access to specific rules – and thereby to the Pāḷi texts themselves – may skip entire chaptersPrimarily the chapters “Sandhi”, “Morphology”, “Kita and Taddhita Affixes” and “Uṇādi Affixes.” and/or the sections on formation contained within most of the remaining ones. They may directly proceed to those parts of the book discussing actual usage, holding the most relevant information for comprehending the syntax and meaning of the Pāḷi text one wishes to understand. Let it be finally remarked, however, that a proven way to gain a broader and deeper grasp of the Pāḷi language is to get also familiar with word formation and derivation principals; therefore, it is recommended.

Pāḷi – Historical Backdrop

Pāḷi is one of the Middle Indo-Aryan (MIA) languages, itself part of the Indo-Aryan language family. The broad classification of Indo-Aryan languages can, on linguistic grounds,This classification scheme is not strictly applicable on historical grounds; MIA languages are older than Classical Sanskrit. be chronologically subdivided in the following way (

- 1500 BCE – 600 BCE: Old Indo-Aryan – Vedic (Ṛgvedic Sanskrit and its dialects), Classical and Epic Sanskrit.

- 600 BC – 1200 CE: Middle Indo-Aryan – Pāḷi, Prākṛt (Prakrit), Ardha-Magadhī, Māharāṣṭrī, Gāndhārī, Sinhala Prakrit, Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit etc.

- 1200 CE – present: New Indo-Aryan – Hindu/Urdu, Sinhala, Dardic, Panjabi, Dogri, Nepali, Bengali etc.

The corpora of early Buddhism have initially and in the first few centuries after the demise of the Teacher been transmitted in four of these Indic languages at a minimum: (1) Pāḷi, (2) Classical Sanskrit, (3) Gāndhārī and (4) Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit (

Basing himself upon morphological and lexical features,

Pāḷi – Derivation and Orthography

The word “Pāḷi”IPA:

Pāḷi – the Name of a Language

Nowhere in the canon (pāḷi), its commentaries (aṭṭhakathā) or sub-commentaries (ṭīkā) preserved within the Pāḷi tradition is mention made of a language with the name “Pāḷi.”It is also unknown to non-Buddhist traditions (

- Māgadhabhāsā – “the language of Magadha” (Mp-ṭ II – dukanipātaṭīkā, p. 178).E.g.: Sammāsambuddhopi hi tepiṭakaṃ buddhavacanaṃ tantiṃ āropento māgadhabhāsāya eva āropesi – “Surely, when the the Perfectly Enlightened One committed the Buddha Word, the tipiṭaka, to the canon, it was done just by means of the language of Magadha (māgadhabhāsāya).”

- Māgadhavohāro – “the current (or ‘popular’) speech of Magadha” (Kkh, p. 39).E.g.: Ettha ca ariyakaṃ nāma māgadhavohāro.

Levman on the term vohāro (personal communication, April 28, 2020): “The word vohāro is derived from OI [Old Indian] vy- ava + hṛ, meaning ‘to carry on business’, ‘trade’, ‘deal in’, ‘exchange’, ‘have intercourse with’ etc. In other words, the very word vohāro confirms the existence of this koine.” What this “koine” is referring to is elaborated upon further down below. - Māgadhiko vohāro – “the speech belonging to Magadha” (Sp IV – cūḷavagga-aṭṭhakathā, p. 23).[S]akāya niruttiyā ti ettha sakā nirutti nāma sammāsambuddhena vuttappakāro māgadhiko vohāro.

- Māgadhikā bhāsā – “the language belonging to Magadha” (Moh, p. 75).Sabhāvaniruttīti ca māgadhikā bhāsā, yāya sammāsambuddhā tepiṭakaṃ buddhavacanaṃ tantiṃ āropenti – “‘The natural tongue’: the language belonging to Magadha, with which the Perfectly Enlightened Ones commit the Buddha Word – the tipiṭaka – to the canon.”

- Ariyako – “Aryan [language].”

- Ariyavohāro – “the current Aryan speech” (Sp I – pārājikakaṇḍa-aṭṭhakathā, p. 94).E.g.: [T]attha ariyakaṃ nāma ariyavohāro, māgadhabhāsā.

This nomenclature landscape makes for the rationale behind selecting the title of the present grammar as it stands, despite most (but not all) scholars’ dislike of adopting that name for the language in which the lore of Pāḷi Buddhism was transmitted and in which it has been committed to writing – a language which was possibly even used by the Buddha himself (more on that further below in the section “Pāḷi – What is it?”). How, then, did it come about that we nowadays know that language under the name “Pāḷi” in the first place and not as it was known throughout, likely already in the nascent years of Buddhism?

For

Pāḷi – What is it?

The Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics (

The above-presented traditional accounts, reporting the language as found in the texts of the Pāḷi Buddhist tradition to be māgadhabhāsā etc., are by and large considered incorrect by modern scholars. They adduce, inter alia, the peculiar features of the Māgadhī dialect proper as inferred from the Aśokan inscriptions and the medieval descriptions of it by the Indian grammarians and determined these features to be (a) l instead of r (e.g. lāja – rāja), (b) a-stems in e for o (e.g. lāje – rājo) and (c) palatal ś for dental s. However, based upon inscriptional and other evidence,

A consensus of opinion regarding the home of the dialect on which Pāli is based has therefore not been achieved. Windisch therefore falls back on the old tradition and I am also inclined to do the same according to which Pāli should be regarded as a form of Māgadhī, the language in which Buddha himself had preached.

What emerges from the above is that the traditional narrative should not be and has not been dismissed outright.

Commentaries, Sub-Commentaries and Pāḷi Grammatical Literature

The aṭṭhakathā and ṭīkā traditions take the language of Magadha (māgadhabhāsā) to be a natural language – a delightful language indeed (Sv-pṭ – sīlakkhandhavaggaṭīkā, p. 6).Manoramaṃ bhāsa nti māgadhabhāsaṃ. As presented already above, the Samantapāsādikā vinaya aṭṭhakathā (Sp IV – cūḷavagga-aṭṭhakathā, p. 23) proffers the following annotation of the phrase sakāya niruttiyā as used by two Brahmins in the context of one cardinal (as it relates to linguistics) incident recorded in the vinaya, where they, still attached to things Vedic, complain about the way or language by adopting or use of which the Buddha’s teaching was spoiled: “[…] herein ‘own tongue’ is certainly the common speech belonging to Magadha (māgadhiko vohāro) in the manner spoken (vuttappakāro) by the Perfectly Enlightened One.”[…] ettha sakā nirutti nāma sammāsambuddhena vuttappakāro māgadhiko vohāro. The 12/13ᵗʰ century CE Vimativinodanīṭīkā (Vmv, p. 125) interprets the relevant portion of the episode thus: “They ruin (dūsenti) the word of the Buddha with their own language (sakāya niruttiyā) as it relates to the canon (pāḷi): ‘Surely, those of inferior birth who learn [memorize; the buddhavacana] are ruining [it] with the language of Magadha (māgadhabhāsāya) to be spoken by all with ease (sabbesaṃ vattuṃ sukaratāya)’ – this is the meaning.”Pāḷiyaṃ sakāya niruttiyā buddhavacanaṃ dūsentīti māgadhabhāsāya sabbesaṃ vattuṃ sukaratāya hīnajaccāpi uggaṇhantā dūsentīti attho. The Vinayālaṅkāra-ṭīkā (Pālim-nṭ, p. 180) from the 1600’s CE in turn as succinctly as possible glosses sakāya niruttiyā as māgadhabhāsā, the “language of Magadha.”Sakāya niruttiyā ti māgadhabhāsāya. The Samantapāsādikā on another occasion (Sp I – pārājikakaṇḍa-aṭṭhakathā, p. 94) equates māgadhabhāsā seemingly with the Aryan language as a whole, thereby possibly referring to a supra-regional language.[T]attha ariyakaṃ nāma ariyavohāro, māgadhabhāsā. The indigenous Pāḷi grammars basically concur with the above. The Padarūpasiddhi, for example, mentions explicitly that the Buddha spoke a tongue belonging to Magadha (māgadhika), as recorded in the tipiṭaka (

In this connection it appears relevant to mention that the aṭṭhakathā tradition is not just an alternative scholarly opinion but rather constitutes strong additional evidence (cf.

[…] some parts of the commentaries are very old, perhaps even going back to the time of the Buddha, because they afford parallels with texts which are regarded as canonical by other sects, and must therefore pre-date the schisms between the sects. As has already been noted, some canonical texts include commentarial passages, while the existence of the Old Commentary in the Vinaya-piṭaka and the canonical status of the Niddesa prove that some sort of exegesis was felt to be needed at a very early stage of Buddhism.

Furthermore, Buddhaghosa’s Samantapāsādikā contains over 200 quotations of earlier material, according to the indigenous tradition harkening back in parts to the first council (paṭhamasaṅgīti) held shortly after the demise of the Buddha (

[…] Pāli should be regarded as a form of Māgadhī […] Such a lingua franca naturally contained elements of all the dialects […] I am unable to endorse the view, which has apparently gained much currency at present, that the Pāli canon is translated from some other dialect (according to Lüders, from old Ardha-Māgadhī). The peculiarities of its language may be fully explained on the hypothesis of (a) a gradual development and integration of various elements from different parts of India, (b) a long oral tradition extending over several centuries, and (c) the fact that the texts were written down in a different country. I consider it wiser not to hastily reject the tradition altogether but rather to understand it to mean that Pāli was indeed no pure Māgadhī, but was yet a form of the popular speech which was based on Māgadhī and which was used by Buddha himself.

Whatever the case may be when it comes to the nature of Pāḷi, perhaps

Pāḷi and the Buddha

The Pāḷi canon does not contain any record about which language the Buddha spoke, either as his native tongue, regarding potential standard dialects, a lingua franca or a koine. As a Sakyan, having possibly been nothing less than “junior allies”That this term might be a viable alternative rendering for the commonplace “vassals” to denote the relationship between the Sakyan crowned republic and the Kosalan kingdom might be gathered from Pj II (

This much suffices to understand that “vassal” is a rendering which misses out on a number of possible nuances. The respective glosses found in the Sumaṅgalavilāsinī and its ṭīkā make a rendering as “junior ally” even more compelling. The former explains anuyuttā with vasavattino (“wielding power”, “dominating”), but the latter clarifies this term – commenting on the textual variant – to mean anuvattakā (“siding in with”, “one who follows or acts according to”). Bryan Levman (personal communication, July 11, 2020) suggest that: “here vasa must have the meaning of OI vaśa ‘willing, submissive, obedient, subject to or dependent on’ (MW),” but finds that the traditional exegeses represents a “commentarial apology” and that it is “trying to make palatable something unpalatable.” It appears to me, however, that the matter, as pictured above, does not seem to justify probative statements. of the Kosalan kingdom, he possibly spoke an eastern Indic dialect as his native tongue but having received a thoroughgoing education in an aristocratic or royal family, he in all likelihood was multilingual (cf.

The Pāḷi Alphabet or Orthography (saññā)

There are 41 phonemes to be found in the Pāḷi language, with the sequential order of them being as follows (

(a) The vowel a is appended traditionally to the consonants for ease of utterance, but a representation without them is also acceptable, perhaps even preferable (

Pāḷi Alphabet Classification

(a) In the traditional classification system we find, to facilitate reference, a division into five groups – called vaggā (pl.) in Pāḷi – of the majority of consonants, according to the position of the tongue in producing the respective sounds (

- Vowels (sarā) – 8

- a, ā, i, ī, u, ū, e, o

- Consonants (byañjanā) – 33

- ka-group (kavaggo) – ka, kha, ga, gha, ṅa.

- ca-group (cavaggo) – ca, cha, ja, jha, ña.

- ṭa-group (ṭavaggo) – ṭa, ṭha, ḍa, ḍha, ṇa.

- ta-group (tavaggo) – ta, tha, da, dha, na.

- pa-group (pavaggo) – pa, pha, ba, bha, ma.

- UngroupedAs per

Ñāṇadhaja (2011, p. 8). (avaggā) – ya, ra, la, va, sa, ha, ḷa. - aṃ.

(a) Only the first and second and the third and fourth letters of the same class (in that order; e.g. ka + kha but not kha + ka) can be conjoined to form a conjunct consonant (here geminates only). (b) The fifth letter (nasal) of each class can be appended to any consonant of the same classification – including itself – to form conjuncts. An exception is the letter ṅ, which cannot form a geminate consonant with itself (

Pāḷi Alphabet – General Descriptions

Vowels

(a) Short (rassaṃ) or light (lahu) are: a, i, u generally as well as e and o before geminate consonants (kkh, cch, kk, yy etc.; e.g. bhāseyya – “He should speak”). Exceptions for e and o: occurrences before conjuncts with end-group nasals are long (e.g. meṇḍo – “sheep”; soṇḍo – “drunkard”; see above the last letters of each group for the end-group nasals). (b) According to the so-called law of mora, long vowels are usually not followed by conjunct consonants (one exception out of many is: svākkhāto – “well taught”) — mora being a translation of the Pāḷi term mattā (“measure”). (c) One mattā denotes the time it takes to pronounce one short vowel, two mattā it takes for a long one as well as a short vowel before geminate and conjunct consonants (e.g. n akkh amati – “He does not approve of”, Sp V – parivāra-aṭṭhakathā, p. 56;

(a) LongVowel length is indicated by the diacritic sign called a “macron” (¯) above the vowel. (dīghaṃ) or heavy (garu) are: ā, ī, ū generally as well as e and o at the end of words (e.g. vane – “in the forest”; putto – “son”), before single consonants (e.g. kāmesu – “regarding sensuality”; odanaṃ – “rice”) and, again, the nasal conjuncts mentioned just above (Sp V – parivāra-aṭṭhakathā, p. 56;

There are differences in opinion regarding the points just mentioned, even among the ancient grammarians. Kaccāyana, for example, mentions e and o as only being long (

With modern examples based upon American English pronunciation (whenever possible), the following lists tender illustrations of articulating letters in accordance to the parameters as found in the Pāḷi language. The letters in parentheses are International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) symbols (“Pali”, n.d.), modelled after the explanations of the ancient grammarian as to the place (ṭhānaṃ), instrument (karaṇaṃ) and mode of articulation (payatanaṃ), given here to broaden the avenues for identification. The underlined parts of the words correspond phonetically.

Consonants

(a) Consonants are said to indicate the meaning. (b) Standing by themselves they take half a mattā to enunciate, with a short vowel one and a half mattā and with a long vowel two and a half (

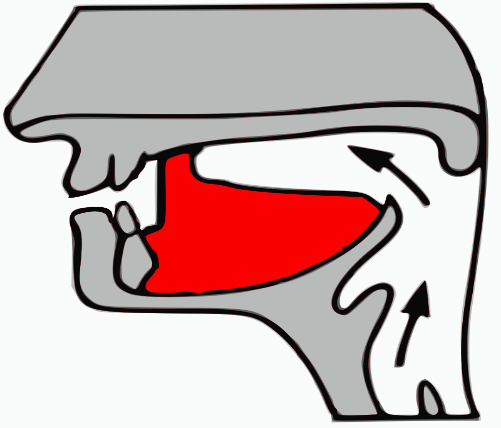

Pāḷi Alphabet: Articulation

Gutturals (kaṇṭhaja)

(a) The letters of this groupKaṇṭhaja, lit. “throat-born.” are a, ā, ka, kha, ga, gha, ṅa, ha and their articulation takes place in the region of the throat, being gutturals (

- a

[ɐ] = nut; - ā

[aː] = calm.

- ka

[k] = luck. - kha

[kʰ] ~ keel, with stronger breath pulse.

- ga

[ɡ] = gear. - gha

[ɡʰ] ~ gear, with breath pulse as with kha.

- ṅa

[ŋ] = thing. - ha

[h] = behind.

Palatals (tāluja)

(a) The letters of this groupTāluja, lit. “palate-born.” are i, ī, ca, cha, ja, jha, ña, ya and their articulation takes place on the palate with the tongue’s middle (instead of its tip) in contact with it (

- i

[ɪ] = sit. - ī

[iː] = seek.

- ca

[tʃ] = which. - cha

[tʃʰ] ~ check, with stronger breath pulse.

- ja

[dʒ] = range. - jha

[dʒʱ] ~ range, with breath pulse as with cha.

- ña

[ɲ] = señor. - ya

[j] = yes.

Cerebrals/Retroflexes (muddhaja)

(a) The letters of this groupMuddhaja, lit. “head-born.” are ṭa, ṭha, ḍa, ḍha, ṇa, ḷa, ra and engendered with near the tip of the tongue, curled back at the roof of the mouth’s interior (

- ṭa

[ʈ] = heart. - ṭha

[ʈʰ] ~ barter, with stronger breath pulse.

- ḍa

[ɖ] = warder. - ḍha

[ɖʰ] ~ warder, with breath pulse as with ṭha.

- ṇa

[ɳ] = barn. - ḷa

[ɭ] = curl. - ra

[ɻ] = ram.

Dentals (dantaja)

(a) The letters of this groupDantaja, lit. “tooth-born.” are ta, tha, da, dha, na, la, sa and sounded with the tip of the tongue in contact with the edge of the row or line of the teeth (

- ta

[t̪] = hit this. - tha

[t̪ʰ] ~ attack, with stronger breath pulse and the tongue in dental position.

- da

[d̪] = rod thin. - dha

[d̪ʰ] ~ den, with breath pulse as with tha and the tongue in dental position.

- na

[n̪] = tenth. - la

[l̪] = wealth. - sa

[s] = salt.

Labials (oṭṭhaja)

(a) The letters of this groupOṭṭhaja, lit. “lip-born.” are u, ū, pa, pha, ba, bha, ma and spoken in contact with both lips (

- u

[u] = put. - ū

[uː] = fruit.

- pa

[p] = stop. - pha

[pʰ] ~ prawn, with stronger breath pulse.

- ba

[b] = hub. - bha

[bʰ] ~ hub, with breath pulse as with pha.

- ma

[m] = moon.

Gutturo-palatal (kaṇṭhatāluja)

(a) The letter is e and its articulation happens in the throat (as with all other vowels) and the palate (

- e

[ɛ] = fell. - e

[eː] = Seele (German).I am not aware of any American English equivalent.

Gutturo-labial (kaṇṭhoṭṭhaja)

(a) The letter is o and is produced in the throat (as with all other vowels) and the lips, with an effort to keep the lips open (

- o

[o] = oko (Czech).See previous footnote. - o

[oː] ~ home (hoʊm; corresponding to[o] before the sound change to[ʊ] ).

Dento-labial (dantoṭṭhaja)

(a) The letter is va and is generated with the teeth and the lips (

- va

[v] = vine. - va

[w] = wind.

The Pure Nasal (niggahītaṃ)

(a) This letter (aṃ)The letter a is, again, just added for ease of pronunciation. is called niggahītaṃ or anunāsiko in PāḷiIn Pāḷi there is no difference between the anunāsiko and the niggahītaṃ, both can be used interchangeably. This can be gathered from numerous passages where the anunāsiko stands for the niggahītaṃ. To quote the Paramatthajotikā I (p. 63) as an example, relating that the anunāsiko, there clearly representing the niggahītaṃ, was inserted for metrical reasons: sabbattha sotthiṃ gacchantī ti […] anunāsiko cettha gāthābandhasukhatthaṃ vuttoti veditabbo. (

- International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration (IAST): ṃ.As in the Romanized editions of the Chaṭṭhasaṅgāyana (Sixth Buddhist Council) and also in those of the later Pali Text Society.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO; ISO 15919): ṁ.This rendition also corresponds to the Unicode character.

- Indian Languages Transliteration (ITRANS): M; N; .m.

- Velthuis: .m.

(a) The niggahītaṃ is capable of forming homorganic nasals, i.e. the place of articulation when pronouncing the niggahītaṃ is assimilated to that of the end-group nasals in the Pāḷi alphabet, thereby being displaced by them, these and the niggahītaṃ thus becoming distinct phonetically (

- ṅ before a velar stop (k, kh, g, gh).

- ñ before a palatal stop (ca, cha, ja, jha).

- ṇ before a retroflex stop (ṭa, ṭha, ḍa, ḍha).

- n before a dental stop (ta, tha, da, dha).

- m before a labial stop (pa, pha, ba, bha).

(a) The place of articulation in the case of the niggahītaṃ is the nose (n āsikaṭṭhānaja – “born in the place of the nose” or nāsikaja – “nose-born”;

(a) The Padarūpasiddhi mentions that this phoneme is called niggahītaṃ because the place of articulation (karaṇaṃ) is restrained (niggahīta, past passive participle of niggaṇhāti – “press”, “repress”) by an obstructed opening (mukhenāvivaṭena) and because it is based upon (nissāya) the short vowels a, i, u, taking them up (gayhati, passive form of gaṇhāti – also “seize”, “acquire”, “grasp”;

(a) Scholars who investigated the phonetic reality of the niggahītaṃ now also seem to regard it as a nasalization of the short vowels a, i, u (

- aṃ

[ã] = “genre.” - iṃ

[ɪ̃] = “vin.” - uṃ

[ũ] = “un.”

(c) That this phenomenon of vowel nasalization is the correct interpretation is furthermore corroborated by the probability of it not having been a foreign element in the major autochthonous language groups present during the floruit of the Buddha. (d) These groups are the ancestral prototypes of modern languages in which this is a recognized feature (as in Dravidian Tamil or Santali). (e) In a similar way this holds true for nasal assimilation (see above).

(a) What emerges from the above is that the pronunciation of the niggahītaṃ as it is commonly realized in the traditional Buddhist countries (in Sri Lanka and Thailand as

Sandhi

(a) Sandhi denotes the process of euphonic (or “pleasing”, “harmonious”) changes that may occur when two letters meet during the formation of words and compound words (

- Vowel sandhi (sarasandhi): meeting of two vowels, as final and initial member.

- Consonantal sandhi (byañjanasandhi): meeting of final vowel and initial consonant.

- Niggahītasandhi: meeting of the niggahītaṃ (ṃ) as final member and vowel or consonant as following initial.

- Natural sandhi (pakatisandhi): retention of the structural pattern with no union taking place.

(a) The rules for the blending of two consonants also belong to the category of sandhi (

- → = “becomes”, “changes into”, “results in.”

- → Ø = elision.

- Ø → = insertion.

- / = “in the environment of.”

- + = meeting.

- # = word boundary.

- [] = optionality (only after symbols).

- (V̆) = short vowel.

- (V̄) = long vowel.

- (C) = consonant.

- (CC) = double consonant.

(a) The underscores (__) indicate the position in the environment where the action happens that is expressed as a rule before the slash; for example, the formula: “vowel → (V̄) [usually] / __ vowel [same class]” says that any vowel (vowel) in the environment before another vowel (/__ vowel) of the same class is usually lengthened (→ (V̄) [usually]). (b) If it should express that the lengthening would happen after (instead of before) another vowel, one would simply change the element “/__ vowel” as above to “/ vowel __”, with the underscores in the posterior position. (c) If there is some additional rule after a comma, following the element which occurs after the slash, that indicates that it applies to this element when the change of the pre-slash rule has occurred or simultaneously (e.g. “vowel → Ø [occasionally] / __vowel, vowel → (V̄)” means after the vowel has been elided – which happens occasionally – when coming before another vowel, that last-mentioned vowel is also lengthened (vowel → (V̄)). (d) To give two other general examples to facilitate comprehension:For exemplification of explicit instances see just below. “vowel → Ø [usually] / o __” signifies that a vowel is usually elided in the environment after the vowel o. Formula “v → b / # __” means that v changes into b after the beginning of a word – in the following the respective rules in full.

Vowel Sandhi (sarasandhi)

- Vowel → Ø / __vowel (e.g. yassa + indriyāni → yassindriyāni;

Kacc 12). - Vowel / __dissimilar vowel, dissimilar vowel → Ø (e.g. cakkhu + indriyaṃ → cakkhundriyaṃ;

Kacc 13). - Vowel → Ø [occasionally] / __vowel, vowel → (V̄) (e.g. tatra + ayaṃ → tatrāyaṃ;

Kacc 15). - Vowel (V̆) → (V̄) [occasionally] / __ vowel, vowel → Ø (e.g. vi + atimānenti → vītimānenti;

Kacc 16). - a or ā → Ø [occasionally] / __ i or ī, i or ī → e (e.g. upa + ikkhati → upekkhati;

Kacc 14). - a or ā → Ø [occasionally]/ __ u or ū, u or ū → o (e.g. canda + udayo → candodayo;

Kacc 14).- Exceptions

- a → (V̄) / __ iti, i → Ø (e.g. tassa + iti → tassāti).

- a / __ i, i → Ø (e.g. pana + ime → paname).

- ā → Ø / __ i (e.g. seyyathā + idaṃ → seyyathidaṃ).

- Vowel (V̆, V̄) → (V̄) [usually] / __ vowel [same class] (e.g. a + a → ā; i + ī → ī; ū + u → ū).

- Vowels before particles beginning with a, i, e (e.g. atha, iva, eva) follow the rules of sandhi thus:

- itthī + iti → itthīti.

- e / __ e, e → Ø (e.g. sabbe + eva → sabbeva).

- o → Ø / __ e (e.g. so + eva → sveva).

- a → Ø / __ ettha (e.g. na + ettha → nettha).

- e → Ø / __ dissimilar (V̄) (e.g. me + āsi → māsi).

- e → Ø / __ dissimilar (V̆) followed by (CC) (e.g. sace + assa → sacassa).

- Vowel → Ø [usually] / o __ (e.g. cattāro + ime → cattārome).

- Vowel (V̄) → (V̆) [occasionally] / __ eva, eva → ri (e.g. yathā + eva → yathariva;

Kacc 22). - abhi → abbh / __ dissimilar vowel (e.g. abhi + uggacchati → abbha uggacchati → abbhugacchati;

Kacc 44, 46). - ti → c [occasionally], c → cc (e.g. iti + etaṃ → iccetaṃ;

Kacc 19, 28, 47). - di → jj / __ dissimilar vowel (e.g. nadī + ā → najjā).

- adhi → ajjha / __ dissimilar vowel (e.g. adhi + okāse → ajjhokāse;

Kacc 45).

Transformation into Semi-Vowels (ādeso)

- i → y / __ dissimilar vowel (e.g. vi + ākāsi → vyākāsi;

Kacc 21). - e [of me, te, ke, ye etc.] → y / __ a followed by (CC) (e.g. ke + assa → kyassa).

- e [of me, te, ke, ye etc.] → y / __ a followed by (C), a → (V̄) (e.g. me + ahaṃ → myāhaṃ: cf.

Kacc 17).- Exceptions

- e → Ø / __ vowel (V̄) (e.g. me + āsi → māsi).

- e → Ø / __ vowel (V̆) followed by (CC) (e.g. sace + assa → sacassa).

- e / __ vowel, vowel → Ø (e.g. te + ime → teme).

- e → Ø / __ a → (V̄) (e.g. sace + ayaṃ → sacāyaṃ).

- u → v [occasionally] / __ dissimilar vowel (e.g. anu + eti → anveti;

Kacc 18). - o → v [occasionally] / __ dissimilar vowel (e.g. yo + ayaṃ → yvāyaṃ;

Kacc 18).- Exceptions

- u → Ø / __ dissimilar vowel (e.g. sametu + āyasmā → sametāyasmā).

- u → (V̄) / __ i (e.g. sādhu + iti → sādhūti).

- o → Ø [usually] / __ vowel (V̄) followed by (CC).

- o → Ø / __ vowel (V̆) followed by (CC) (e.g. kuto + ettha → kutettha).

Consonantal Insertion (āgamo)

- To avoid a hiatus, not seldom the following letters are inserted between two vowels: y, v, m, d, n, t, r, l (= ḷ), h (e.g. na + imassa → nayimassa; √ bhū + ādāya → bhūvādāya; idha + āhu → idhamāhu etc.;

Kacc 35). - Vowel → Ø / __ consonant, Ø → o [occasionally] (e.g. para + sahassaṃ → parosahassaṃ;

Kacc 36). - Vowel / __ vowel or consonant, Ø → ṃ (e.g. ava + siro → avamsiro;

Kacc 37). - Putha, Ø → g [occasionally] / __ vowel, (e.g. putha + eva → puthageva;

Kacc 42). - ā [of pā] → (V̆), Ø → g [occasionally] / __ vowel (e.g. pā + eva → pageva;

Kacc 43).

Consonantal Sandhi (byañjanasandhi)

- Vowel (V̄) → (V̆) [occasionally] / __ consonant (e.g. yiṭṭhaṃ vā hutaṃ vā loke → yiṭṭhaṃ va hutaṃ va loke;

Kacc 26). - Vowel (V̆) → (V̄) / __ consonant (e.g. √ su + rakkhaṃ → sūrakkhaṃ).

- Vowel (V̆) / __ consonant, (C) → (CC) (e.g. idha + pamādo → idhappamādo; usually after: u, upa, pari, ati, pa, a, anu, etc.)

- Vowel (V̆) → (V̄) [occasionally] / __ consonant (e.g. muni + care → munī care;

Kacc 25). - Vowel → Ø and is replaced by a [occasionally] / __ consonant (e.g. eso dhammo → esa dhammo;

Kacc 27). - Vowel → bb / __ v (e.g. ni + vānaṃ → nibbānaṃ).

- Vowel / __ consonant, consonant (C) → (CC) (e.g. idha pamādo → idhappamādo;

Kacc 28). - Vowel (V̄) [of particles] → (V̆) [usually] / __ reduplicated consonant (e.g. ā + kamati → akkamati).

- o [of so, eso, ayo, mano, tamo, paro, tapo and a few others] → a [occasionally] / __ consonant (e.g. esa dhammo; sa attho; ayapattaṃ).

- ava → o [occasionally] / __ consonant (e.g. ava + naddha → onaddha;

Kacc 50). - dha → da [occasionally] / __ vowel (e.g. ekaṃ + idha + ahaṃ → ekamidāhaṃ;

Kacc 20). - dha → ha [occasionally] (e.g. rudhira → ruhira;

Kacc 20). - d → t (e.g. sugado → sugato;

Kacc 20). - t → ṭ (e.g. pahato → pahaṭo;

Kacc 20). - t → k (e.g. niyato → niyako;

Kacc 20). - t → dh (e.g. gantabba → gandhabbo;

Kacc 20). - tt → tr (e.g. attajo→ atrajo;

Kacc 20). - tt → cc (e.g. batto → bacco;

Kacc 20). - g → k (e.g. hatthupaga → hatthupaka;

Kacc 20). - r → l (e.g. paripanno → palipanno;

Kacc 20). - y → j (gavayo → gavajo).

- y → k (e.g. saye → sake;

Kacc 20). - vv → bb (e.g. kuvvato → kubbato;

Kacc 20). - k → y (sake pure → saye pure).

- j → y (nijaṃputtaṃ → niyaṃputtaṃ;

Kacc 20). - k → kh (nikamati → nikhamati;

Kacc 20). - p → ph (e.g. nipatti → niphatti;

Kacc 20). - pati → paṭi [occasionally] / __ vowel (

Kacc 48). - putha [inter alia] → puthu / __ consonant (

Kacc 49).

Niggahīta Sandhi

- ṃ / __ consonant (e.g. taṃ dhammaṃ kataṃ).

- ṃ → respective nasal: ṅ, ñ, ṇ, n, m [occasionally] / __ consonant (e.g. raṇaṃ + jaho → ranañjaho; taṇhaṃ + karo → taṇhaṅkaro; saṃ + ṭhito → saṇṭhito;

Kacc 31). - ṃ → l / __ l (e.g. paṭi + saṃ + līno → paṭisallīno; saṃ + lekko → sallekho).

- ṃ → ñ [occasionally] / __ e [or h] (e.g. taṃ + eva → taññeva; evaṃ + hi → evañhi;

Kacc 32; for doubling of the consonant see under “Consonantal Sandhi (byañjanasandhi)”, pt. 7.;Kacc 28). - ṃ → ñ [occasionally] / __ y (e. g. saṃ + yuttaṃ → saññuttaṃ;

Kacc 33; for doubling of the consonant see under “Consonantal Sandhi (byañjanasandhi)”, pt. 7.;Kacc 28). - ṃ → d [occasionally] / __ vowel (e.g. etaṃ + attho → etadattho;

Kacc 34). - ṃ → m [occasionally] / __ vowel (e.g. taṃ ahaṃ → tamahaṃ;

Kacc 34). - ṃ → Ø [occasionally] / __ consonant (e.g. ariyasaccānaṃ + dassanaṃ → ariyasaccānadassanaṃ;

Kacc 39). - ṃ → Ø [occasionally] / __ vowel (e.g. tāsaṃ + ahaṃ santike → tāsāhaṃ santike;

Kacc 38). - Vowel → Ø [occasionally] / ṃ __ (e.g. kiṃ + iti → kinti;

Kacc 40). - Vowel → Ø, consonant (CC) → consonant (C) / ṃ __ (e.g. evaṃ assa → evaṃsa;

Kacc 41). - Ø → ṃ / __ vowel [or consonant] (e.g. ava siro → avaṃsiro;

Kacc 37).

Natural Sandhi (pakatisandhi)

- Vowel / __ consonant (e.g. mano + pubbaṅgamā → manopubbaṅgamā;

Kacc 23). - Vowel / __ vowel (e.g. ko imaṃ;

Kacc 24). - i [and u] / __ any verb w/ vowel initial (e.g. gāthāhi ajjhabhāsi).

- i [and u] / __ any verb.

- Vowel / __ vocative case (e.g. kassapa etaṃ).

- Final long vowel remains unchanged if not followed by iti or not being compounded.

- Vowel / __ particle w/ initials other than a, i, e. (e.g. atha kho āyasmā).

Morphology

Assimilation

(a) The following morphological changes happen mostly in the formation of the passive, past passive participle, the stems built from the third class root affixes, of the infinitive, absolutive, the future passive participle and in the formation of the desiderative – also under the influence of certain affixes in the derivation of nouns.See chapters “Kita and Taddhita Affixes” and “Uṇādi Affixes.” (b) Regressive assimilation (←) is the more common. (c) The ṇ placed traditionally before all causative affixes to denote vowel increase (vuddhi) in the root (see below the chapter “Vowel Gradation”) is always to be elided (e.g. √ kara + ṇaya + ti → kārayati;

- MuteMute because they require closure or contact (phasso) in their place of articulation and the stopping of the breath. Not to be confused with surd, i.e. unvoiced consonants. They are: k, kh, g, gh, c, ch, j, jh, ṭ, ṭh, ḍ, ḍh, t, th, d, dh, p, ph, b, bb. As with the letters in the alphabet, the a appended to the Pāḷi roots provided is just for ease of utterance. → mute / mute __ (e.g. √ saja + ta → satta).

- Dental → guttural / guttural __ (e.g. √ laga + na → lagna → lagga).

- Dental voiceless → cerebral / palatals __ (e.g. √ maja + ta → maṭṭha or maṭṭa); j and c → t [occasionally] / __ t (e.g. √ bhuja + ta → bhutta; √ muca + ta → mutta).

- Dental voiceless → cerebral / cerebral __ (e.g. √ kuṭṭa + ta → kuṭṭha).

- Dental → consonant / __ consonant (e.g. √ uda + gaṇhāti → uggaṇhāti).

- Voiced aspirate → voiced unaspirate / __ t, t → dh (e.g. √ rudhi + ta → rud + dha → ruddha).

- Voiceless unaspirated guttural or labial → voiceless dental / __ voiceless dental (e.g. √ tapa + ta → tatta).

- Voiced or voiceless unaspirated dental → labial / __ labial (e.g. tad + purisa → tappurisa).

- n → Ø [occasionally ṃ] / __ ta (of past passive participle; e.g. √ mana + ta → mata).

Assimilation of y

Assimilation of this type happens mostly in the formation of the passive voice, absolutives, verbal bases/stems of the third class and derived nouns.

- Consonant ← y (e.g. √ divu + ya → divva → dibba). Also in the middle of a compound word (e.g. api + ekacce → apyekacce → appekacce).

- vv → bb (e.g. √ divu + ya → divva → dibba).

- ā [of √ dā, √ pā, √ hā, √ mā and √ ñā] → eyya [occasionally] / __ ya (e.g. √ dā + ya → deyyaṃ – “something to give”;

Kacc 544). - Ø → ya [occasionally] / da- and dha-ending roots __ tuna, tvāna and tvā [suffixes] (e.g. u + pada + ya + tvā → uppajjitvā;

Kacc 606). - ty → cc (e.g. √ sata + ya → satya → sacca).

- dy → jj (only after √ mada and √ vada; e.g. √ mada + ya → madya → majja;

Kacc 544). - dhy → jjh (e.g. √ rudha + ya → rudhya → rujjha).

- thy → cch (e.g. tath + ya → tathya → taccha).

- my → mma (

Kacc 544). - jy → gga (e.g. √ yuja + ya → yogga;

Kacc 544). - y → sibilant / sibilant __ (e.g. √ pasa + ya → pasya → passa).

- v → b / # __ (e.g. vi + ākaraṇaṃ → vyākaraṇaṃ → byākaraṇaṃ).

- Dental → y / __ y (e.g. √ ud + yuñjati → uyyuñjati).

- u → (V̄) [of √ guha and √ dusa] / __ causative affixes (e.g. √ guha + aya + ti → gūhayati – “causes to protect”, “hide”;

Kacc 486). - ya → abba / √ bhū __ (e.g. √ bhū + ya → bhabbo;

Kacc 543). - a and v [of √ vaca, √vasa , √ vaha] → u [occasionally] / __ ya (e.g. √ vaca + ya + ti → vuccati;

Kacc 487). - Initial vowels [of √ dā, √ dhā, √ mā, √ ṭhā, √ hā, √ pā, √ maha, √ matha] → ī / __ ya (e.g. dā + ya + ti → dīyati;

Kacc 502). - Consonant y [of √ yaja] → i / __ ya (e.g. √ yaja + ya + ti → ijjate – “He is worshipped”;

Kacc 503).

Assimilation of r

- r → Ø / __ mute (e.g √ kara + ta → kata).

- r → Ø, a → (V̄) / __ mute (incl. lengthening of preceding a; e.g. √ kara + tabba → kātabba).

- n → ṇ/r __, r → ṇ (e.g. √ cara + na → carṇa → ciṇṇa).

- r → l / __ l (e.g. dur + labho + si [o] → dullabho).

- When any r-morpheme is appended to a root, the first component vowel of that root and its last consonant are usually elided as well the vowel and the r of the r-morpheme (

Kacc 539).

Assimilation of s

- j + sa → kkh / __ sa (e.g. bubhuj + sa → bubhukkha).

- p + sa → c ch / __ sa (e.g. jigup + sa → jiguccha).

- t + sa → cch / __ sa (e.g. tikit + sa → tikiccha).

- s + sa → cch / __ sa (e.g. jighas + sa → jighaccha).

- y → s [occasionally] / sa __ (e.g. √ nasa + ya → nassa; alasa + ya + si [aṃ]→ ālasyaṃ).

- t → ṭ / s __ (e.g. √ kasa + ta → kaṭṭha).

- Dental → s / __ s (e.g. √ uda + sāha → ussāha).

- s → t / __ t (e.g. √ jhasa + ta → jhatta).

- s → tth / __ t (e.g. √ vasa + ta → vuttha).

Assimilation of h

- Consonant → aspirated consonant / __ h (e.g. √ uda + harati → uddharati).

- hṇ → ṇh/ __ ṇ (e.g. √ gaha + ṇa → gahṇa → gaṇha).

Kacc 490 explains it like this: h [of √ gaha] → Ø when Ø → ṇhā (e.g. gaṇhāti). - h

↔ y and in some instances ya → la (e.g. oruh + ya → oruyha;Kacc 488). - h

↔ v (e.g. jihvā → jivhā). - h → y [seldom]/ __ y (e.g. leh + ya → leyya).

- h → gh [occasionally] / #__ (e.g. hammati → ghammati).

- h + t → ddh (e.g. √ duha + ta → duddha).

- h + t → dh (sometimes; e.g. √ liha + tuṃ → ledhuṃ).

Reduplication

- The second and fourth consonants of the consonant groups (sing. vaggo) are added to the first and third respectively (e.g. yatra ṭhitaṃ → yatraṭṭhitaṃ;

Kacc 29).Exceptions: idha, cetaso, daḷhaṃ, gaṇhāti, thāmasā. - Initial vowel [of roots] → (V̄) (e.g. √ ah → āha).

- The reduplicated vowels → i, ī and a [occasionally] (e.g. jigucchati;

Kacc 465). - A guttural is reduplicated by its corresponding palatal (e.g. √ kita + cha + ti → cikicchati;

Kacc 462). - An unaspirate is always reduplicated by an unaspirate (e.g. √ chida → ciccheda – “It was cut”;

Kacc 458, 462). - An aspirate is reduplicated by its unaspirate (e.g. √ bhuja → bubhukkhati;

Kacc 458, 461). - The initial h of a root is reduplicated by j (e.g. √ hā → jahāti;

Kacc 464). - v is reduplicated by u [usually] (e.g. √ vasa → uvāsa).

- a or ā takes a (e.g. √ dhā → dadhā;

Kacc 460). - i or ī takes i [occasionally] (e.g. √ kita → cikicchā;

Kacc 460). - u or ū takes u but occasionally a (e.g. √ bhū → babhuva).

- i → e [occasionally] (e.g. √ chida → ciccheda).

- u → o [occasionally] (e.g. √ suca → susoca).

- a [of a root] → (V̄) (e.g. √ vada → uvāda).

- m [of √ māna] → v [occasionally] / __ reduplicated vowel (e.g. vīmaṃsati;

Kacc 463). - √ māna → maṃ [occasionally] / reduplicated vowel __ sa (e.g. vīmaṃsati;

Kacc 467). - √ pā → vā [occasionally] / reduplicated vowel __ sa (e.g. pivāsati;

Kacc 467). - Reduplicated k [of √ kita] → t / __ reduplicated vowel (e.g. tikicchati;

Kacc 463). - Ø → ṃ [occasionally] / reduplicated vowel __ (e.g. caṅkamati;

Kacc 466).

Further Morphological Changes

- √ pā → pivā [occasionally] (e.g. √ pā + ā + ti → pivati;

Kacc 469). - √ ñā → jā, jaṃ, nā [occasionally] (e.g. √ ñā + a + ti → jānāti;

Kacc 470). - √ disa → passa, dissa, dakkha [occasionally] (e.g. √ disa + a + ti → passati;

Kacc 471). - √ hara → gī / __ sa (e.g. jigīsati;

Kacc 474). - √ brū and √ bhū change into āha and bhūva respectively / __ perfect endings (e.g. √ brū + a → āha;

Kacc 475). - m [of √ gamu] → cch [occasionally] / __ all conjugational root affixes (e.g. √ gamu + a + māna + si [o] → gacchamāno;

Kacc 476). - Initial vowel [of √ vaca] → o / __ aorist suffix (e.g. √ vaca + uṃ → avocuṃ;

Kacc 477). - ū [of √ hū] → eha, oha, e [occasionally] / __ future tense suffix, future tense suffix may → Ø (e.g. √ hū + ssati → hehiti;

Kacc 480). - √ kara may → kāha [occasionally] / __ future tense suffix, future suffix → Ø (

Kacc 481). - ā [of √ dā] → aṃ / __ present tense suffixes mi and ma (e.g. √ dā + mi → dammi;

Kacc 482; ṃ → m byKacc 31). - Non-conjunct root vowels → increaseSee below the chapter “Vowel Gradation” for details. [usually] / __ non-causative affixes (e.g. √ hū + a + ti → hoti;

Kacc 485). - Ø → kha, cha, sa [occasionally] / √ tija, √ gupa, √ kita and √ māna __ (e.g. √ tija + kha + ti → titikkhati – “He forbears [or ‘endures’]”;

Kacc 433). - √ gaha → ghe / __ affix ppa (e.g. gheppati;

Kacc 489). - √ kara → kāsa [occasionally] / __ aorist suffix (e.g. √ kara + ī → akāsi;

Kacc 491). - Suffix mi → mhi [occasionally] / √ asa __ (e.g. √ asa + mi → amhi – “I am”;

Kacc 492). - Suffix ma → mha [occasionally] / √ asa __ (e.g. √ asa + ma → amha – “We are”;

Kacc 492). - Suffix tha → ttha [occasionally] / √ asa __, s [of √ asa] → Ø (e.g. √ asa + tha → attha – “You are”;

Kacc 493). - Suffix ti → tthi [occasionally] / √ asa __ (e.g. √ asa + ti → atthi – “[there] is”;

Kacc 494). - Suffix ti → ssa / √ asa __ (e.g. √ asa + ti → assa – “It should be”;

Kacc 571). - Ø → i / √ brū __ ti (e.g. √ brū + a + ti → bravīti – “He says”;

Kacc 520). - Suffix tu → tthu [occasionally] / √ asa __ (e.g. √ asa + tu → atthu – “Let it be”;

Kacc 495). - s of [of √ asa] → Ø when nominative suffix siThis nominative suffix undergoes changes to o, aṃ etc. in other cases. is appended to √ asa (e.g. √ asa + si → asi – “You are”;

Kacc 496). - Aorist suffixes ī → ttha / √ labha __ (e.g. √ labha + ī → alattha;

Kacc 497) - iṃ → tthaṃ / √ labha __ (e.g. √ labha + iṃ → alatthaṃ;

Kacc 497). - Aorist suffix ī → cchi / √ kusa __, s [of √ kusa] → Ø (e.g. √ kusa+ ī → akkocchi – “He reviled”;

Kacc 498). - √ dā → dajja [occasionally] (e.g √ dā + eyya → dajjeyya;

Kacc 499). - √ vada → vajja [occasionally] (e.g. √ vada + eyya → vajjeyya;

Kacc 500). - √ gamu → ghamma [occasionally] (e.g. √ gamu + a + tu → ghammatu – “Let him go”;

Kacc 501). - Aorist suffix uṃ → iṃsu / all roots __ (

Kacc 504). - √ jara → jīra or jiyya [occasionally] (e.g. √ jara + a + ti → jīrati;

Kacc 505). - √ mara → miyya [occasionally] (e.g. √ mara + a + ti → miyyati;

Kacc 505). - Initial vowel a [of √ asa] → Ø [occasionally] / __ all suffixes (e.g. √ asa + a + anti → santi;

Kacc 506). - √ asa → bhū [occasionally] (e.g. √ asa + a + ssanti → bhavissanti;

Kacc 507). - Optative suffix eyya → iyā or ñā / √ ñā __ (

Kacc 508). - Affix nā (fifth class active base root affix) → Ø or ya [occasionally] / √ ñā __ (

Kacc 509). - Affix a (first class active base root affix) → Ø or e [occasionally] (e.g. √ vasa + a + mi → vademi;

Kacc 510). - Affix o (seventh class active base root affix) → u [occasionally] / √ kara __ (e.g. √ kara + o + te → karume – “He does”;

Kacc 511). - Component vowel a [of √ kara] → u [occasionally] (e.g. √ kara + o + ti → kurute – “He does”;

Kacc 511, 512). - The increase morpheme o → ava / √ bhū, √ cu etc. __ vowel (e.g. √ cu + a + ti → cavati;

Kacc 513).See also below the chapter “Vowel Gradation” for details. - The increase morpheme e → aya / √ nī, √ ji etc. __ vowel (e.g. √ ji + a + ti → jayati;

Kacc 514). - Increase vowel o → āva, e → āya / __ causative affix [e, ya] (e.g. √ lū + e + ti → lāveti;

Kacc 515). - Ø → i / root consonant __ asabbadhātuka suffixesSuffixes of the perfect (parokkhā), aorist (ajjatanī), future indicative (bhavissanti) and conditional (kālātipatti) are meant (

Kusalagñāṇa , 2012, p. 161). (e.g. √ gamu + ssati → gamissati;Kacc 516). - Last component vowel [of polysyllabic roots] → Ø [occasionally] (e.g. √ mara + a + ti → marati;

Kacc 521). - Consonants s and m [of √ isu, √ yamu] → cch [occasionally] (e.g. √ isu + a + ti → icchati;

Kacc 522). - ima → a, samāna → sa / ima, samāna, apara __ suffixes jja, jju jja, jju (e.g. ima + jja → ajja – “today”).

- Kita affix ta → cca or ṭṭa / √ naṭa __ (e.g. √ naṭa + ta + si [aṃ] → naccaṃ – “dancing”;

Kacc 571). - Regarding kita affix ta:

- √ sāsa, √ disa → riṭṭha / __ ta (e.g. √ disa + ta → diṭṭha – “seen”;

Kacc 572). - ta → ṭṭha [together with final root consonant] / √ puccha, √ bhanja, √ hansa and roots ending in s etc. __ (e.g. √ bhanja + ta → bhaṭṭha;

Kacc 573). - ta → uṭṭha [together with final s of the root] / √ vasa __ , v → u [occasionally] (e.g. √ vasa + ta → vuṭṭha;

Kacc 574–575). - ta → dha and ḍha respectively / dha, ḍha, bha, ha __ (e.g. √ budha + ta + si [o] → buddho – “the Awakened One”;

Kacc 576). - ta → gga [together with final j of the root] / √ bhanja __ (e.g. √ bhanja + ta → bhagga – “broken”;

Kacc 577). - ta → (CC) / √ bhanja etc. __, final root consonant → Ø (e.g. √ caja + ta → catta – “given up”:

Kacc 578). - ta → (CC) / √ vaca __, v [of √ vaca] → u [occasionally], c → Ø (e.g. √ vaca + ta → utta – “said”;

Kacc 579). - ta → (CC) / √ vaca __, v [of √ vaca] → u [occasionally], c → Ø, Ø → v (e.g. √ vaca + ta → vutta – “said”;

Kacc 579). - ta → (CC) / √ gupa etc. __, final root consonsants → Ø (e.g. √ lipa + ta → litta – “annointed”;

Kacc 580). - ta → iṇṇa / √ tara etc. __, final root consonants → Ø (e.g. saṃ + √ pūra + ta → sampuṇṇa – “well-filled”;

Kacc 581). - ta → inna, anna, īṇa / √ bhida etc. __, final root consonants → Ø (e.g. √ bhida + ta → bhinna – “broken”;

Kacc 582). - ta → nta [occasioanlly] / prefix pa etc. + √ kamu etc. __, final root consonants → Ø (e.g. pa + √ kamu + ta → pakkanta;

Kacc 584). - ta → kkha and kka / √ susa, √ paca, √ saka etc. __, final root consonants → Ø (e.g. √ susa + ta → sukkha – “dried”;

Kacc 583). - ta → ha / ha-ending roots (except √ daha and √ naha) __, h [of the roots] → ḷ (e.g. √ baha + ta → bāḷha – “grown”;

Kacc 589).

- √ sāsa, √ disa → riṭṭha / __ ta (e.g. √ disa + ta → diṭṭha – “seen”;

- Initial a [of √ yaja] → i / __ ṭṭha (morphological resultant of ta; e.g. √ yaja + ta → yiṭṭha;

Kacc 610; see also pt. b above for changes which result in ṭṭha). - Final consonants [of ha, da, bha of √ naha, √ kudha, √ yudha, √ sidha, √ labha, √ rabbha etc.] → da / __ dha (morphological resultant of ta; e.g. √ labha + ta → laddha – “obtained”;

Kacc 611; see also pt. d above for changes which result in dha). - Final component consonants ha, ḍha [of √ daha, √ waḍha] → ḍa / __ ḍha (morphological resultant of ta; e.g. √ daha + ta → daḍḍha – “burnt”;

Kacc 612; see also pt. d above for changes which result in ḍha). - Regarding kita affixes ta and ti:

- Initial vowel [of √ jana] → ā / __ ta or ti (e.g. √ jana + ta → jāta – “born”, “arisen”;

Kacc 585). - Final root consonant [of √ gamu, √ khanu, √ hana, √ ramu etc.] → Ø [occasionally]/ __ ta or ti (e.g. √ khanu + ti → khati – “digging”;

Kacc 586). Exception: Ø → i as per pt. 64 below (Kacc 617). - Final r [of √ kara, √ sara etc.] → Ø / __ ta or ti (e.g. pa + √ kara __ ti → pakati – “original [or ‘natural’] form”;

Kacc 587). - Vowel ā [of √ ṭhā, √ pā etc.] → i or ī respectively / __ ta or ti (e.g. √ pā + ti → pīti – “act of drinking”;

Kacc 588).

- Initial vowel [of √ jana] → ā / __ ta or ti (e.g. √ jana + ta → jāta – “born”, “arisen”;

- ta [of kita affix tabba] → raṭṭha / √ sāsa, √ disa etc. __ (e.g. √ disa + tabba + si [aṃ] → daṭṭhabbaṃ;

Kacc 572, elision of r according toKacc 539). - tuṃ suffix → raṭṭhum / √ sāsa, √ disa etc. __ (e.g. √ disa + tuṃ = daṭṭhuṃ;

Kacc 573; elision of r according toKacc 539). - Regarding kita affix ṇa:

- nja [of √ ranja] → j / __ ṇa (

Kacc 590). - √ hana → ghāta / __ ṇa (e.g. go + √ hana + aka + si [o] → goghātako – “the one who kills cows”;

Kacc 591). - √ hana→ vadha / __ ṇa (e.g. √ hana + ṇa + si [o] → vadho – “the one who kills”;

Kacc 592). - vowel ā [of ā-ending roots] → āya / __ ṇa (e.g. √ dā + aka + si [o] → dāyako – “a donor”;

Kacc 593).

- nja [of √ ranja] → j / __ ṇa (

- √ kara → kha / pura, saṃ, upa and pari __ (e.g. saṃ + √ kara + ta → saṅkhata – “conditioned”, “prepared”;

Kacc 594). - √ kara → kā / __ kita suffixes tave and tuna (e.g. √ kara + tuna → kātuna – “having done”;

Kacc 595). - m and n [of √ gamu, √ khanu, √ hana etc.] → n [occasionally] / __ kita affixes tuṃ and tabba (e.g. √ gamu + tabba + si [aṃ] → gantabbaṃ – “that which should be done”;

Kacc 596). - kita suffixes tuna, tvāna, tvā etc.:

- → ya [occasionally] / after all roots __ (e.g. ā + √ dā + tvā → ādāya;

Kacc 597). - → racca [occasionally] / all ca- and na-ending roots __ (e.g. vi + √ vica + tvā → vivicca – “having renounced”, “being far from”;

Kacc 598). - → svāna, svā [occasionally] / √ disa __ (e.g. ā + √ disa + tvā → disvā;

Kacc 599). - → mma, yha, jja, bbha, ddha [occasionally] ma-, ha-, da-, bha-ending roots __ (e.g. ā + √ gamu + tvā → āgamma – “having come”;

Kacc 599).

- → ya [occasionally] / after all roots __ (e.g. ā + √ dā + tvā → ādāya;

- Ø → i / root __ all affixes (ririya, tabba, ta, tvā etc.; e.g. √ vida + tabba → viditabba;

Kacc 605). - The first n [of some roots] → ṃ (e.g. √ ranja + ṇa + si [o]→ raṅgo – “act of coloring”;

Kacc 607). - √ ge → gī [whenever appropriate] (e.g. √ ge + ta + si [aṃ] → gītaṃ – “music”;

Kacc 608). - √ sada → sīdā [always] (e.g. ni + √ sada + a + ti → nisīdati;

Kacc 609). - √ gaha → ghara [occasionally] / __ affix ṇa. (e.g. √ gaha + ṇa + si [aṃ] → gharaṃ – “house”;

Kacc 613). - da [of √ daha] → ḷa [occasionally] / __ affix ṇa (e.g. pari + √ daha + ṇa + si [o] → pariḷāho – “burning”;

Kacc 614). - Final consonant [of a root] → Ø / __ kita affix kvi (i.e. other roots themselves;

Kacc 615). - Ø → ū / √ vida __ kita affix kvi (e.g. lokavidū – “the knower of the world”;

Kacc 616). - (a) When an inserted i (as per

Kacc 605) is already positioned, the final consonants [of √ hana, √ gamu, √ ramu, √ saka, √ kara etc.] are not elided with ta affixes. (b) Applicable affixes are: tabba, tuṃ, tvā and tvāna. (c) Inapplicable exceptions are: tave, tāye, tavantu , tāvi and teyya (Kacc 617;Thitzana , 2016, p. 756). - r [of √ kara] → t / __ tu (e.g. √ kara + ritu + si [→ Ø] → kattā – “the one who does”;

Kacc 619). - r [of √ kara] → t [occasionally] / __ tuṃ, tuna, tabba (e.g. √ kara + tuna → kattuna;

Kacc 620). - The final component consonant c [of √ paca etc.] and j [of √ yaja etc.] → k and g respectively / __ affix ṇa (e.g √ yuja + ṇa + si [o]→ yogo;

Kacc 623) but not / __ ṇvu affixes (Kacc 618).

Uṇādi Rules

- Initial vowel [of √ gaha] → ge [occasionally] (e.g. √ ga ha + a + si [aṃ]→ gehaṃ – “house”;

Kacc 629). - su [of stem masu] → cchara or cchera (e.g. masu + kvi + si [o]→ maccharo – “jealousy”;

Kacc 630). - √ cara → cchariya, cchara or cchera / ā __, ā → (V̆) (e.g. ā + √ cara + kvi + si [aṃ] → accharaṃ;

Kacc 631). - tha [of √ matha] → la (e.g. √ math a + a + si [o]→ mallo – “wrestler”;

Kacc 634). - Some roots which end in c and j → k and g respectively / __ ṇ-initial affix (e.g. √ sica + ṇa + si [o] → seko – “pouring”;

Kacc 640). - una [of stem suna – “dog”] → oṇa, vāna, uvāna, ūna, unakha, una, ā or āna (

Kacc 647). - Stem taruṇa → susu (

Kacc 648). - uva [of stem yuva] → uvāna, una, or ūna (e.g. yūno – “youth”;

Kacc 649). - ū, u and asa [of √ sū, √ vu, √ asa] → ata, Ø → affix tha (√ sū + tha + si [aṃ] → satthaṃ – “a weapon”;

Kacc 660). - √ hi → heraṇ or hīraṇ / paṭi __ (e.g. paṭi + √ hi + kvi + si [aṃ] → pāṭihīraṃ or pāṭiheraṃ – “miracle”;

Kacc 662). - Stem putha → puthu, patha, Ø → affix amaFor an example refer to the section “Ordinal Numerals.” [occasionally] (e.g. putha + kvi [→ Ø] + si [→ Ø] → pathavī – “earth”;

Kacc 666).

Vowel Gradation

(a) Root vowels may vary in “strength” or appear in various “grades”, which means that they are changed into another vowel sound. (b) This process is called “strengthening” or “vowel gradation” and occurs regularly in the formation of verbal stems, non-finite verbs (i.e. infinitives and absolutives) and in the derivation of words while appending certain affixes (see chapters “Kita and Taddhita Affixes” and “Uṇādi Affixes”;

- Unstrengthened (avuddhika).

- Strong (guṇa).

- Increase (vuddhi).

(a) The ancient grammarians explain these processes as an absence and prefixing (or “increase”) of the letter a respectively (

| Unstrengthened | Strong | Increase |

|---|---|---|

| – | a | ā |

| i, ī | e, aya | e, āya |

| u, ū | o, ava | o, āva |

Parts of Speech (padajāti)

- Nouns – incl. adjectives and pronouns (nāmāni).

- Verbs (ākhyātāni).

- Indeclinable prepositions and prefixes (upasaggā or upasārā).

- Indeclinable particle – conjunctions, prepositions, adverbs and all other indeclinables (nipātā).

Sentence Structure and Syntax

(a) The main collections (sing. nikāyo) of Buddhist texts employ an idiom which usually bears a close affinity to the syntax of Vedic, thereby manifesting a closer linguistic connection to Indo-European than Classical Sanskrit; however, marked divergences from Vedic nevertheless exist (cf.

(a) A regular yet not universal feature of prose portions in the Pāḷi language (as well as Vedic and Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit) is the grouping of word elements with related or identical meaning (e.g. synonyms), a remnant of the oral style of composition and transmission, facilitating memory (

- They simply follow each other.

- Relative clauses and phrases:

- With relative pronouns, adjectives or adverbs as the sentence initial of the subordinate clause, in correlation with a demonstrative pronoun, adjective or adverb introducing the main clause (e.g. yo dhammaṃ passati so buddhaṃ passati – “He who sees the dhamma is the one who sees the Buddha”; Mil, p. 35).

- With a participle functioning as an adjective agreeing with a noun (e.g. addasā kho āyasmā rāhulo bhagavantaṃ dūratova āgacchantaṃ – “The ven. Rāhula saw the Blessed One, who was coming from afar”, MN II – majjhimapaṇṇāsapāḷi, p. 40 [MN 61]).

- With dependent-determinative, descriptive-determinative or attributive compoundsSee chapter “Compounds (samāsā)” for details. (e.g. evaṃ kho, kassapa, bhikkhu sīlasampanno [tappurisa compound] hoti – “thus, Kassapa, is a bhikkhu one who is possessed of virtue”, DN I – sīlakkhandhavaggapāḷi, p. 81 [DN 8]).

- With the introduction of adverbs or adverbial phrases of time and space (e.g. tadā – “at that time”; tattha – “there”; bhūtapubbaṃ – “formerly”; ekaṃ samayaṃ – “at one time”; tena samayena – “at that time”; atha kho – “now then” etc.)

- With particles ca (copulative) and vā (disjunctive).

- Phrase kuto pana (“still less”) and words pageva (“still more”), aññādatthu (“except”; all adversative).

- With seyyathāpi (“just as”) contrasted with evameva (“just so”) and yathā (“just as”), contrasted with tathā (“so”; all comparatives).

- Consecutive and connected verbs may stand in the absolutive with the finite verb being placed last.

(a) It may often happen that the verb “to be” is not expressed but only implicitly understood (e.g. rūpaṃ aniccaṃ – “Form is impermanent”). (b) In the end, there are no hard and fast regulations about the sentence structure – the subject, to proffer an example, remains the subject even if it succeeds the object (e.g. dhammaṃ buddho [S] deseti – “Dhamma teaches the Enlightened One [S]”;

Nouns (nāmāni)

Kinds of Nouns

- Substantive Nouns (nāmanāmāni).Sing. nāmaṃ.

- Common nouns (sādhārananāmāni).

- Proper nouns (asādhārananāmāni).

- Adjectives (guṇanāmāni).

- Pronouns (sabbanāmāni).

- Compound nouns (samāsanāmāni;

Kacc 601). - Nouns formed from taddhita affixes (taddhitanāmāni, incl. numerical nouns;

Kacc 601). - Nouns formed from kita affixes (kitanāmāni;

Kacc 601).The last three-mentioned items are dealt with in separate chapters.

General Characteristics

(a) In the Pāḷi language there are no fundamentally distinct classes of substantive nouns, adjectives and pronouns, all being united under the broad category of nāmaṃ (noun), but individual differences nonetheless exist (

- Sāriputto; Arindamo (nāmanāmaṃ, kitanāmaṃ and samāsanāmaṃ).

- Kaccāyano (nāmanāmaṃ and taddhitanāmaṃ).I am indebted to ven. Kovida (Myanmar, aka Sayadaw U Kovida) for initially clarifying the concept for me and providing the examples (personal communication, April 11, 2020).

(a) Although adjectives bear the name of guṇanāmaṃ (“quality noun”) – indicating that they are a class of nouns qualifying other nouns – the lack of an absolute distinction between substantive nouns and adjectives can be seen in many instances; for example, the word kusala (“wholesome”, “skillful”) can stand as a substantive noun: kusalaṃ (“the wholesome”) or operate as an attribute of another noun, as in kusalo dhammo (“the good dhamma”). (b) Compound nouns are simply combinations made up of members from the above-given noun classes (see the respective chapters for details). (c) Although particles (sing. nipāto) and prefixes (upasaggo or upasāraṃ) cannot be classified under the rubric of nouns – possessing no gender and number – they can be subject to the rules of nouns when standing as independent words in a sentence; these are, however, exceptional cases (

General Formation

The formation of nouns in the Pāḷi language comes about in the following manner, conjoining two or more of these elements:

- Prefix (upasaggo or upasāraṃ).

- Root (dhātu).

- Kita affix (kitapaccayo).

- Taddhita affix (taddhitapaccayo).

- Interfix (āgamo).

- Suffix (paccayo, vibhatti), expressing:

- Case.

- Number.

- Gender.

(a) For example, the substantive noun āvāso is formed from these elements: ā (upasaggo) + √ vas + a [kita affix] form the stem to which si [o] (vibhatti; singular nominative case masculine suffix) is appended; thus, finally → āvāso (“home”, “dwelling place”). (b) Another example to illustrate how an interfix is applied is given with the following. The adjective mānasika is broken up like this: √ māna + s [āgamo] + ika [taddhita affix] → mānasika (“related to mind”) or + si [aṃ] (singular nominative case neuter sufffix – “that which is related to mind”) when functioning as a substantive noun. (c) Another interfix, consonant n, is added in the formation of numerical nouns with dative suffix naṃ (e.g. dvinnaṃ – “two”;

Gender, Number and Case

(a) In the Pāḷi language three genders (sing. liṅgaṃ) exist for nouns: masculine (pulliṅgaṃ), feminine (itthiliṅgaṃ) and neuter (napuṃsakaliṅgaṃ;

Substantive Nouns (nāmanāmāni)

As mentioned above, this classification includes common and proper nouns (cf.

- Common nouns: a group of unspecified people (vāṇijo – “merchant”), animals (hatthī – “elephant”), places (nagaraṃ – “city”), things (rukkho – “tree”) and ideas (i.e. abstract nouns; dhammo – “norm”, “nature”).

- Proper nouns: specific persons (Sāriputto – right-hand chief disciple of Lord Buddha), places (Rājagaha – an ancient Indian city with that name) and organizations.

(a) As single entities, substantive nouns have usually merely one gender (of the three, as mentioned above), but as final members of attributive compoundsSee chapter “Compounds (samāsā)” for details. substantive nouns can also assume all three genders – in which case they are used adjectivally (

Adjectives (guṇanāmāni)

(a) As adverted to earlier, adjectives bear the name of guṇanāmāni (“quality nouns”), indicating that they are a class of nouns modifying other nouns, providing more information about them (

(a) Pronouns or pronominal adjectives are used as adjectives (

Three Grades of Adjectives

(a) To express the comparative form of adjectives, the following affixes are appended to nominal bases: tara, iya, iyya and for the superlative: tama, iṭṭha, issika, (i) ma (

| (Positive) Natural Adjective (pakatikaguṇanāmaṃ) |

(Comparative) Distinctive Adjective (visesaguṇanāmaṃ) |

(Superlative) Beyond-Distinctive Adjective (ativisesaguṇanāmaṃ) |

|---|---|---|

| abhirūpa (“beautiful”) |

abhirūpatara (“more beautiful”) |

abhirūpatama (“most beautiful”) |

| dhanavant (“rich”) |

dhavantatara (“richer”) |

dhanavantatama (“richest”) |

| pāpa (“evil”) |

pāpīya/pāpiyya (“eviler”) |

pāpiṭṭha/pāpissika (“most evil”) |

| Note: Substantive nouns in nt take a before tara and tama, forming the alternative stem in anta. Sources: (a) |

||

Participles

The participles have the nature of verbal adjectives and must, therefore, agree with the nouns they qualify in number, gender and case (

Possessive Adjectives

Formation. (a) Commonly added are vantu (vā), vī (

Usage. (a) The possessive adjectives can be rendered into English as regular adjectives or in combination with such words and idioms as “having”, “possessed of”, “possessing” (e.g. satimā – “possessed of mindfulness [i.e. ‘mindful’]”;

Adjectives from Pronominal Bases

(a)

Pronouns or Pronominal Adjectives (sabbanāmāni)

Kinds of Pronouns

- Personal pronoun (puggalanāmaṃ).

- Demonstrative pronoun (nidassananāmaṃ).

- Relative pronoun (anvayīnāmaṃ).

- Interrogative pronoun (pucchānāmaṃ).

- Indefinite pronoun (anīyamanāmaṃ).

- Possessive pronoun (

Collins , 2006, p. 61;Nwe Soe , 2016, p. 205;Perniola , 1997, p. 52).

General Characteristics

(a) Substantive nouns and adjectives may qualify their referent words, but pronouns act as mere pointers to these (

General Formation

(a) For a description on the general features of the formation process of nouns (incl. pronouns), see the above section of the present chapter having the same name as this one (i.e. “General Formation”), with some additional specifics in the following. (b) The i and a vowels of pronouns may lengthen when in certain combinations with √ disa, so too then vowel i of √ disa (e.g. ya + √ disa + kvi → yādiso – “any kind of person”;

The Traditional Inventory of 27 Pronouns (sabbanāmāni)

- sabba

- “all”

- katara

- “which [of two]?”

- katama

- “which [of many]?”

- ubbaya

- “both”

- itara

- “other [of two]”

- añña

- “other [of many]”

- aññatara

- “other [of many]”

- aññatama

- “a certain [of two]”

- pubba

- “former”

- para

- “another”

- apara

- “another”

- dakkhiṇa

- “right”, “south”

- uttara

- “upper”, “north”, “more than”

- adhara

- “lower”

- ya

- “who”, “what”

- ta

- “he”, “that”

- eta

- “this”

- ima

- “this”

- amu

- “that”

- kiṃ

- “what?”, “why?”

- eka

- “one”

- ubha

- “both”

- dvi

- “two”

- ti

- “three”

- catu

- “four”

- tumha

- “you”

- amha

- “I”, “we”

Personal Pronouns

Usage. (a) Personal pronouns of the first and second persons do not possess gender and invariably operate as substantive noun substitutes (

Demonstrative Pronouns

Usage. (a) The pronouns of absence, formed from the stem ta(d), are employed to refer to someone or something previously mentioned in a narrative or to absent persons or things.Pronoun ena is used in the same way (

(a) Demonstrative pronouns formed from pronominal stem eta(d) are used to point to someone or something present in direct speech or to what immediately precedes or follows – they may be translated as “this” etc. (

(a) Demonstrative pronouns formed from the pronominal stem in ima (such as ayaṃ) are used similarly but convey a special sense of proximity or immediacy, whereas those constructed from eta(d) are merely indefinite (

Relative Pronouns

Formation. (a) Relative pronouns are mainly found building relative clauses (e.g. yo dhammaṃ passati, so buddhaṃ passati – “He who sees the dhamma is the one who sees the Buddha”, Mil, p. 35), but some are employed as indeclinables (

Usage. (a) Relative pronouns are commonly translated with “who” or “which”, in the three genders. (b) As a simple marker of a relative clause or a connector of a subordinate clause it may function as an indeclinable and be translated as “that”, “since”, “if”, “whereas” etc. (e.g. nesa dhamma, mahārāja, yaṃ tvaṃ gaccheyya ekako – “It is not right, great king, that you might go alone”, Jā II – dutiyo bhāgo, p. 188 [Jā 547];

- Repetition of ya(d) and the correlative in a distributive sense (e.g. yo yo […] ādiyissati, tassa tassa dhanamanuppadassāmi – “Whoever will take up, to him I will give”, DN III – pāthikavaggapāḷi, p. 27 [DN 26]).

- In combination with its correlative (e.g. yasmiṃ tasmiṃ – “in whatever place/case”).

- In combination with the indefinite pronouns (e.g. yaṃ kiñci – “whatever”).

(a) The form yadidaṃ can be employed in a variety of ways (e.g. “that is to say”, “since”, “which is this”, “namely”;

Interrogative Pronouns

Formation and Usage. (a) Interrogative pronouns are used to formulate questions (

Indefinite Pronouns

Formation and Usage. (a) Indefinite pronouns don’t refer to any person, thing or amount specifically. They are inexplicit, “not definite.” (b) Sometimes substantive nouns are constructed from indefinite pronouns (e.g. kiñcanaṃ – “defilement”;

- Addition of ci (cid before a vowel), cana (canaṃ is also found), api or pi to the interrogative pronouns (e.g. kiñci, kācana, kampi).

- Twofold repetition of the demonstrative or relative pronoun (e.g. so so – “anyone”; taṃ taṃ, in the sense of “several”, “various”).

- Joining a relative with an indefinite (e.g. yaṃ kiñci – “whatever”).

- Joining a negative with an indefinite (e.g. na kiñci – “nothing”).

Possessive Pronouns

Formation and Usage. (a) Some possessive pronouns form from the base of the first and second personal pronouns by means of affixes īya and aka, with occasional lengthening of the base vowel (e.g. mad + īya → madīya; mam + aka → māmaka – “mine”;

Pronominal Derivatives (Adjectives, Adverbs)

Adjectives (

Adverbs (

Action Nouns

Formation and Usage. (a) The use of action nouns in Pāḷi is frequent – they are formed with affixes a, i, ana, anā, aka, taṃ, tā, ti, tta,See the chapter “Kita and Taddhita Affixes” for more details. added either directly to the root or the base (

Agent Nouns

Formation. (a) The affixes forming agent nouns are: a, ana, aka, āvi, dha, i, in, ina [after √ ji], ka, ma, ratthu (tar), ta, tra, tuka [after √ gamu], uka, ūSee chapters “Kita and Taddhita Affixes” and “Uṇādi Affixes” for more details. – they are appended to roots or bases (

Usage – as Adjectives and Substantive Nouns. (a) Agent nouns are frequently encountered in Pāḷi (more so in the earlier strata of the language) and may be translated as “one who does” [this or that] or rendered simply by means of the English suffixes -er or -or, denoting someone or something who/which does the action described by the verb, i.e. the agent (e.g. tathāgato […] daṭṭhāraṃ na maññati – “The Tathagata […] does not conceive the doer”, AN IV – catukkanipātapāḷi, p. 16 [AN 4.24];

Usage – as Verbs and Predicates. (a) Agent nouns in Pāḷi may express the main action of a sentence (e.g. samaṇo gotamo, ito sutvā na amutra akkhātā imesaṃ bhedāya – “The ascetic Gotama is not one who relates there what he has heard here for the division of those”, DN I – sīlakkhandhavaggapāḷi, p. 2 [DN 1]). (b) They are also capable of denoting the action of a subordinate clause (e.g. ahaṃ tena samayena purohito brāhmaṇo ahosiṃ tassa yaññassa yājetā – “At that time, I was the king’s high priest, who was the performer of [or ‘who performed’] the sacrifice”, DN I – sīlakkhandhavaggapāḷi, p. 68 [DN 5];

Grammatical Case (vibhatti)

Kinds of Cases

- Nominative (paṭhamā or paccattavacanaṃ).

- Accusative (dutiyā or upayogavacanaṃ).

- Instrumental → ablative of instrument (tatiyā or karaṇavacanaṃ).

- Dative (catutthī or sampadānavacanaṃ).

- Ablative of separation (pañcamī, avadhi or apādānaṃ).

- Genitive or possessive (chaṭṭhī or sāmivacanaṃ).

- Locative (sattamī, bhummavacanaṃ, ādhāro).

- Vocative (ālapana or āmantaṇavacanaṃ).

General Characteristics

(a) Noun case suffixesSee Table 3 in the “Tables” section for a comprehensive listing. are affixed to nominal stems to indicate grammatical case. (b) The traditional Pāḷi grammars acknowledge seven cases in total, excluding the vocative for the overall tally (cf.

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative | si (→ o) | yo (→ ā) |

| Vocative | si (→ Ø) | yo (→ ā) |

| Accusative | aṃ | yo (→ e) |

| Instrumental | nā (→ ena) | hi (→ ebhi) |

| Dative/Genitive | sa (Ø → s) | naṃ (→ ānaṃ)Vowel a [of stem] → (V̄). |

| Ablative | smā (→ mhā, ā)Suffix may remain unchanged. | hi (→ ebhi) |

| Locative | smiṃ (→ mhi, e)Suffix may remain unchanged. | su (final a [of stem] → e / __ su)Suffix may remain unchanged. |

To reiterate, the Padarūpasiddhi (

Usage of the Cases

Nominative

- Subject (kattā – lit. “agent”) of sentences or clauses, active or passive. This is the main use of this case (

Wijesekera , 1936/1993, p. 39). - Subject qualifiers: adjectives (guṇanāmāni), predicates (kiriyāni) or a term in apposition (e.g. [predicate] […] saṅgati phasso – “The meeting … is contact”, MN I – mūlapaṇṇāsapāḷi, p. 80 [MN 18]).

- Items in a ti clause.

- Text titles (e.g. dīghanikāyo).

- Exclamations (of abstract nouns).

- Hanging nominative, introduces another phrase without grammatical connection (

Kacc 281, 285;Collins , 2006, pp. 19–20). - The nominative can also be used instead of the locative (e.g. evaṃ kilesamaladhova , vijjante amatantaḷe. na gavesati ta ṃ ta ḷā ka ṃ , na doso amatanta ḷ eThe respective commentary explicitly identifies kilesamaladhova as a nominative employed in the sense of a locative: kilesamaladhova nti kilesamalasodhane, bhummatthe paccattavacanaṃ (Bv-a, p. 47). I am indebted to Bryan

Levman , who pointed out this passage to me. Both occurrences might be explained on different grounds, so much so that this usage has to be considered unattested (Oberlies , personal communication, October 3, 2020). – “Just so there exists the pool of the deathless for the cleansing of the stains. If you don’t search out that pool, it is not the fault of the pool of the deathless”, Bv, p. 6; bhikkhu nisinne mātugāmo upanisinno […] hoti – “While the bhikkhu is sitting, the woman has sat down closely”, Vin I – pārājikapāḷi, p. 157 [Ay 1]).

Accusative

- Direct object, incl. goal of motion (kammaṃ) – the main function of this case (

Kacc 280;Wijesekera , 1936/1993, p. 58). - Internal direct object (e.g. “He sang a song”).

- With abstract endings ttaṃ and tā as object of verbs of motion or acquisition for change of state.

- Double accusative (e.g. taṃ ahaṃ brūmi brāhmaṇaṃ – “Him I call a Brahmin”, MN II – majjhimapaṇṇāsapāḷi, p. 203 [MN 98]).

- Viewpoint (in the sense of “in terms of”, “as”; e.g. yo ca abhāsitaṃ alapitaṃ tathāgatena abhāsitaṃ alapitaṃ tathāgatenāti dīpeti – “he who explains that which has not been said and spoken by the Tathagata as what was not said and spoken by the Tathagata”, AN II – dukanipātapāḷi, p. 7 [AN 2.24]).

- Various adverbial uses:

- Time during which (e.g. te tattha […] ciraṃ dīghaṃ addhānaṃ titthanti – “They stay there for a long stretch of time”;

Kacc 298). - Extent of space (e.g. yojanaṃ – “for a yojana”;

Kacc 298). - Manner (e.g. sādhukaṃ manasikarohi – “Apply your mind [i.e. ‘pay attention’] thoroughly!”, DN III – pāthikavaggapāḷi, p. 75 [DN 31]).

- Time during which (e.g. te tattha […] ciraṃ dīghaṃ addhānaṃ titthanti – “They stay there for a long stretch of time”;

- Object of various prepositions and postpositions: pacchā, antarā, yathā, vinā, santike, anu, abhi, paṭi (

Collins , 2006, pp. 20–3;Duroiselle , 1906/1997, pp. 155–6). - May be used in the sense of the genitive, ablative,With such words as dūra (“distant”, “far” etc.) instrumental and locative (e.g. [locative] so […] pubbaṇhasamayaṃ nivāsetvā pattacīvaramādāya gāmaṃ vā nigamaṃ vā piṇḍāya pavisati – “He […], having dressed in the morning time and having taken his robe and bowl enters a village or town for alms”, MN II – majjhimapaṇṇāsapāḷi, p. 63 [MN 67];

Kacc 275, 279, 297, 306–307).

Instrumental

- The instruments (means) or thing with which an action is completed; the fundamental use of this case (

Kacc 279;Wijesekera , 1936/1993, p. 108). - Logical subject of passive verbs (e.g. svākkhāto bhagavatā dhammo – “Well taught is the dhamma by the Blessed One”, DN III – pāthikavaggapāḷi, p. 100 [DN 33]).

- Cause or reason (

Kacc 289). - Accompaniment (saddhiṃ and saha are not absolutely necessary; e.g. […] atha kho bhagavā āyasmatā aṅgulimālena pacchāsamaṇena yena sāvatthi tena cārikaṃ pakkāmi – “and then the Blessed One went to Sāvatthi with the venerable Aṅgulimāla as his attendant monk”, MN II – majjhimapaṇṇāsapāḷi, p. 150 [MN 86];

Kacc 286). - Manner.